Sneak Peek: Ashes & Bread

The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming novel Ashes by Tiffini Johnson. Writing isn’t only something I do, it is healing and it holds a very dear place in my heart. This entire blog, including every excerpt of the novels, is copyrighted. Feel free to share a link to the post all you wish but please do not steal my work.

Enjoy!

***********

Maman ran into the fence.

I stare straight ahead at my mother’s stiff body, laying on the ground. I stare, frozen in my spot, while two other prisoners in striped uniforms lift her and lay her in a wheelbarrow. I feel the space inside my chest, where my heart used to be, constrict. I don’t want her there. A thin layer of loose snow covers the wheelbarrow and it will freeze her back. I shuffle my feet and move a little closer to her, trying to find the words that will wake her up. I stop before I get next to her body, though, paralyzed by the expression on her face. Flakes of snow cling to her closed eyelashes, rest upon her sunken cheeks; her pale lips not bent in a frown. Maman looks cold, folded in the wheelbarrow, but peace is written in the lines on her face. She looks peaceful for the first time in… in years.

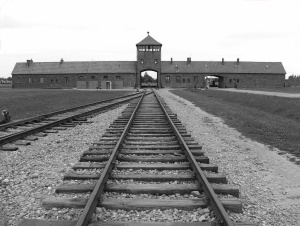

One of the women begins pushing the wheelbarrow. I watch as they roll my mother past me. I shuffle my feet against the snow, turn to watch them push her towards the smoke. Maman will go into the chimney now, she will become the black smoke rising above the gray landscape known as Auschwitz. The sting against the back of my eyes is unfamiliar. I haven’t cried since that first awful night when we were shoved off the trains, greeted by barking dogs and shouting men. But my eyes blur now, as I watch the wheelbarrow pass the barracks. It will round the corner at the end of the street and to the smokehouse by the woods. I want to go with her. I will drop the brick in my hands and run to the wheelbarrow, throw myself in it beside my mother. They would let me. They would stand smiling, smoking cigarettes and warming their hands in their pockets, while I crawled into the oven with my mother. We could both warm ourselves together. We could both be free.

But…

I turn and lay the brick in my hands on top of the mortar, like I’m supposed to do. We are building another barrack. There are more of us coming and they, the black boots, need a place to put them. I can’t feel my toes or my fingers. Maman sang to me. My frozen lips barely move, mouthing the words to the songs she sang. She fought so hard for life. Before the train, before the dogs, before we walked through these gates, this place was the place of our nightmares. For two years, Maman warned me about how much they wanted me and all of us dead. Every time there was a knock on our door, she made me hide in a pile of straw in our cellar. When I threatened to rip the yellow star off my coat, she smacked me, telling me to stop being so stupid, shouting the question, Don’t you know you would be asking to be taken away if you walk out that door without that star? That was our word for this place then…. Taken away. We didn’t know, not even Maman knew, what they did with the people they took, but we knew that if we were taken away, we would not come back.

Maman fought so hard for life, for my life.

Until we were here… until our nightmare came true. Then, when I lay shaking on the barrack, my arm throbbing from where they’d used needles to brand me like an animal, my head cold without my hair, Maman didn’t cry. She put her arm around my belly and pushed my head to her chest and sang to me. The other women on the bunk with us and those on the bunk above us lay perfectly quiet so they could hear her, too. She sang until…she sang until the day came when she didn’t. When I asked her why, she stared blankly ahead into the darkness and said nothing. She didn’t sing after that.

***** **** *****

It’s been four appels since Maman ran into the fence. I do not know how much longer I can take the hard labor. I can’t be sure because I don’t know how to keep track of the months or the years anymore but I think I am twelve years old now. I don’t know what twelve-year-old girls look like or what they are able to do, but I used to be stronger. When I first came here, I was stronger. I could do the work. Now, I have to fight just to stay on my feet. Lifting the bricks gets harder and harder every day.

The whistle should sound any minute now and then we will have appel, the nightly roll call. I am trying to think about that, trying to keep myself moving forward, when the woman who has been working next to me all day collapses. She lies on the ground beside me not moving. No one says anything. The black boots do not see her yet. The Kapos do not see her yet. She may have bread. Before the thought even finishes running through my mind, I quickly lean down and put my hand in her pocket, wrap my fingers around the hard bit of bread. I will have food tonight. Her death is my hope. I stuff the bread into my own pocket as fast as I can, then return to putting the bricks in place. I act like I have not noticed the woman.

I don’t feel guilty. She is dead. She is going into the ovens. She does not need the bread anymore and if I don’t take it another desperate Jew will. It is my bread now. It is my life. You may take from the dead, Maman told me, but you will take nothing from the living. The bread burns a hole in my pocket, I can feel it through my thin uniform. My heart is pounding, the way it does every time I take something from someone who has died. Not because I feel guilty for taking it but because, if I am caught, I will die.

The sound of the whistle is loud. Within minutes, we all become like cattle, scurrying back to the square, trying to avoid the whips by getting in a perfect line. It is roll call. During appel, we stand at attention on one side while the black boots stand on the other side. Surrounding the guards are the bodies of those who died during the day. They have to be accounted for. They are the black boots’ proof of a job well done. I don’t want to stare at them, the bodies, but I can’t help it. I wonder if my mother was put in a pile and counted before she was shoved into the ovens. If she were in a pile and I saw her lying among other dead bodies, would I recognize her? I don’t know…. She would like they all look. She would be another skeleton and I can’t tell any of them apart anymore. They just look dead.

Maman.

How long have I been standing here? Hours. My legs are numb, my fingers are nearly frostbit. I think of the ovens. I can smell the smoke. It is in my skin, it is in my eyes, it is in the air everywhere. I want to be near it because it would thaw me out, it might warm my skin. My eyes start to close, there is a roaring in my head, like a train. Don’t pass out. If you pass out, you die. I force my eyes open, remember the bit of bread in my pocket. Just make it through the appel, then you can eat. The black boots are shouting, people are falling down. Two women just a few people down from me in the line fall. They were alive when appel started and now they are dead.

I don’t know how I last but by the time we are ushered into the barracks, I know for sure that I will die tomorrow if I have to work with the bricks again. I lay on the bunk. I am cold, I am shaking. I pull the bread out of my pocket and stare at it. I hold it in my hands. It is round, it is yellow. It is hard but I know it would start wonderful to me. My stomach has stopped growling but food haunts my every thought. I need to eat the bread. But… I can’t. I can’t because Maman didn’t want me to die, she wanted me to live. And I can’t live working on the building. I put my bread back in my pocket. I shake, bury my head in my arms and close my eyes. I feel like I am crying but there are no tears.

Just the smell of smoke in my nostrils.

***** ***** ******

I know what I have to do with the bread.

We are drug out of our bunks at daybreak and prodded into the line for appel. I follow the crowd, like I do every morning. But I wait for him to come. It is one of the Kapos I need, I know which one. The Kapos are terrifying. They aren’t afraid to torture. But they have power with the black boots, they can move people around the camps, they can get things done for you. But only if you are careful, only if you approach the right ones. If you aren’t careful, the Kapos will get you killed. The one I need comes down the line every morning. He is quiet, he isn’t like the others. He’s never struck me, not once. I trip over my wooden shoes twice looking for him before I am finally in my place. I don’t see him. I scan the gray landscape, looking for his uniform, looking for him. I pray, Don’t let him be gone, don’t let him be in the ovens. I shuffle my feet. Trying to stay still is hard.

There he is! That’s him, he’s coming!

I stand upright, get ready. This might kill me, I could die right now, in the next minute. But it is the only chance I have of getting out of the hard labor, of moving from the bricks. Sometimes, Maman said, You’re dead if you do and you’re dead if you don’t.

He has a baton, he is holding it, looking at every one, counting us. I feel my palms start to itch. I want to take the bread out, I want it to be ready. But I’m too scared. If anyone else sees the bread in my hand, I will be warmed by the ovens. Only when he is standing in front of the person two down from me do I dare sneak my palm into my pocket, grab the bread and try to breathe. He is walking again, here he comes, it’s now or never.

I pretend to stumble, deliberately fall just when he walks in front of me. His baton clubs me in the back, knocking me to the ground, calling me a “filthy pig.” I grab onto his leg. When he bends down to strike my hands away, I whisper urgently, “I have bread.”

He pauses, strikes my hands, but does not stand. Instead, he starts to dust off his uniform. So I whisper quickly, “I won’t live another day if I have to do the bricks again. Isn’t there somewhere else I can go?” I drop the bread at his feet. Within an instant, it is gone and he is standing, moving away from me. He doesn’t look back, but I am not shot, so I have hope. I stand up before a Kapo or a black boot can shoot me for being down, my heart pounding. I follow him with my eyes but he never looks back at me and soon he is gone. My heart sinks. He took my bread. He took my bread. I cling to those words as though they are a rope all morning long.

Appel finishes and we are ordered to breakfast. We sit, wait for the dirty water they call soup to reach us. I still look for the Kapo that has my bread, but hope doesn’t live long here. He took my bread because he could, not because he meant to help me. My head is bowed, looking at my soup when someone kicks me in the back. Soup splashes over the bowl, onto my face, my uniform.

“Move,” the voice is scratchy. I drop my bowl and stand, turning to look.

It is him.

“Come with me,” he says. “You’re being moved.”

My heart soars.

I don’t say anything but walk as I am ordered to do, following him. Soon, he slows his walk and speaks in a quiet tone over his shoulder. “I couldn’t get you in the offices. It’ll still be labor. But maybe it will be better than the bricks.”

“Where will I be?” I dare to ask.

“Barrack 19.”

My shoulders slump. There are four barracks here that are used for the infirmary and Barrack 19 is one of them. Except almost no one gets better in the infirmary, almost no one comes back. The Infirmary; we call it the Waiting Room. The Waiting Room for the Chimneys.